State of the States: Recycling Legislation

The phrase “plastics are everywhere” can be perceived as either a lament of the anti-plastics crowd or the rallying cry of those who see the vast societal benefits of plastics in everyday lives. It can also refer to the number of plastics-related bills at the state level in 2020. Considering bills that have carried over from two-year legislative sessions begun in 2019 and including a range of newly introduced bills, well over 200 separate proposals dealing with some aspect of plastics regulation are currently under consideration.

The underlying themes we continue to see are how to reduce litter and how to eliminate or reduce materials destined for waste disposal. The current focus is on plastic packaging and plastic single-use products like food containers, grocery bags, utensils, etc.

Much of the legislation proposed focuses on what some legislators think is the simplest solution—banning or restricting the use of certain plastics altogether. However, we should all recognize that the solution is never so easy, as any action has some sort of environmental impact, and there is research that plastic bans really aren’t that effective.

At the same time, some states are considering a comprehensive policy change to shift some or all of the economic and operational burden of taking back single-use packaging and products from government collection and disposal systems to an extended producer responsibility (EPR) model.

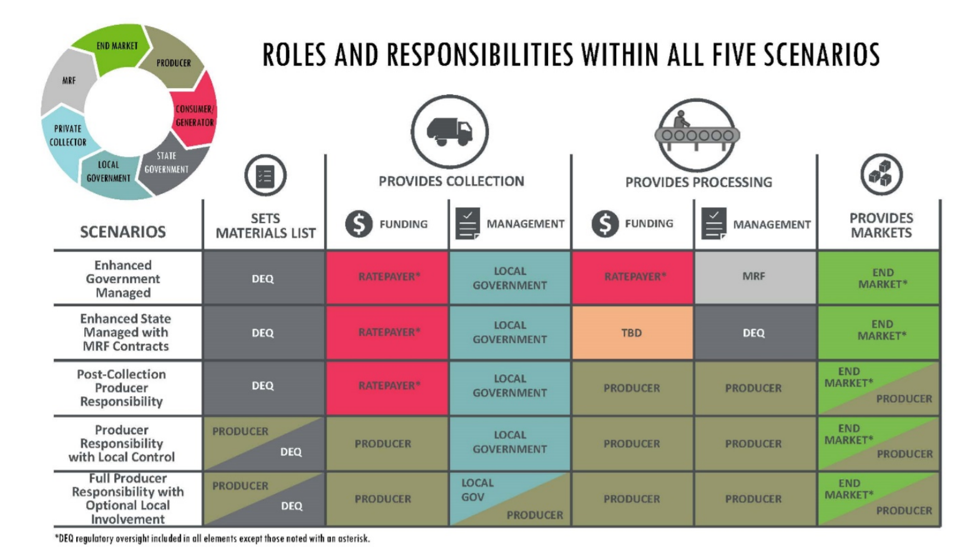

An example of EPR models

Oregon is one state that has begun to investigate an EPR model. The state’s Recycling Steering Committee (RSC) operates under the auspices of the state’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), and a report prepared by Resource Recycling Systems (RRS) is part of a workplan to comprehensively review the state’s recycling programs and produce recommendations to “modernize” the entire system. The recommendations will likely result in proposed legislation in 2021.

The RSS report evaluates five different scenarios. The first two scenarios are centered around tightening state involvement in the current government-controlled recycling system and don’t involve EPR at all; the other three do.

The first would ensure that localities provide recycling services meeting state requirements in all areas where solid waste collection services are offered; would enhance state permitting of material recovery facilities (MRFs); and would establish additional system requirements that would be adopted in all five scenarios such as recycled content mandates and identifying a core list of “recyclables” and banning these items from waste collection.

The second scenario would entail the DEQ taking over the processing component of the recycling chain by contracting directly with MRFs. Local government would continue to control collection.

In the third scenario, producers (identified as brand owners or retailers) would be responsible for managing and funding the recycling processing and marketing system and for funding pre-collection litter abatement and waste reduction programs. Localities would still handle collection. The report assumes that Producer Recycling Organizations (PROs) would form and develop these programs for most individual producers. PROs would collect money from producers based on the costs to implement the EPR plan and would fund and operate the plan elements.

In the fourth scenario, localities would still control recyclables collection, but producers would reimburse them for the full cost in addition to funding customer education, litter control, waste reduction, processing and marketing. And in the last scenario, producers would finance and manage the entire recycling system including all of costs mentioned for scenario four. It is envisioned that producers or their PROs would contract with MRFs and collectors and localities would no longer have operational responsibility or authority over any aspect of the recycling programs.

EPR models are being proposed elsewhere

In 86 pages, the RRS report touches on the brute complexity of some of the changes being considered for Oregon. In the meantime, other states like Maine (LD 2104), Washington, Colorado, New York (S.7718 and A.9790), and Vermont are also considering some form of EPR for packaging, either in ongoing studies or introduced bills authorizing agencies to propose such plans for implementation as soon as 2022. The mega packaging recycling bill in California, SB54/AB1080, which will likely be considered in the next several weeks contains authorization for the CalRecycle state agency to evaluate an EPR system as part of a broad program, as does a competing proposed California ballot initiative that could be qualified for inclusion in the November 2020 elections.

Of ongoing concern to the business community is the enormous amount of authority that would be delegated to state agencies to develop and implement these complicated EPR programs. In order to develop such a system, state bureaucrats—who may or may not have the right expertise—would essentially be picking winners and losers in packaging and product markets that touch almost every aspect of daily life.

VI, our downstream product allies, and the entire plastics chain, no matter the resin type, will have to carefully watch these developments at the state level and participate in the discussions in a meaningful way to ensure reasonable implementation of the types of potentially market-disrupting programs now being discussed.